This article is a part of "CCB Spotlight," a new ongoing series of articles that will report on achievements in research, education, career development, and community development among students, alumni, faculty, staff, groups and wider members of the chemistry and chemical biology community at Harvard. To nominate an individual and or a group to be spotlighted, please complete this short form or reach out to Communications Manager Yahya Chaudhry.

In honor of Women's History Month, this article profiles Rachel H. Lloyd-- the first American woman to earn a PhD in chemistry and a tireless promoter of science education for women.

Early Life:

Rachel H. Lloyd lays claim to many firsts: she was the first American woman to earn a doctorate in chemistry, the first woman to publish in major academic chemistry journals, and the first woman to be regularly admitted to the American Chemical Society. To achieve these firsts required talent, curiosity and fortitude in the face of systemic discrimination against women at a time when women were excluded from the sciences.

Rachel was born on January 26, 1839 in Flushing, Ohio to a large Quaker farming family. By the time she was 12 years old, Rachel had witnessed the deaths of her three siblings and her parents. Rachel recieved an education at public schools in Ohio and Pennsylvania, and upon graduating from Miss Margeret Robinson's School for young ladies, Rachel began teaching science at the school. When she was 20 years old, Rachel married Franklin Lloyd, a chemist with Powers & Weightman who kept a laboratory in their house, piquing her interest in chemistry.

The couple had two children who died in infancy, and Franklin died shortly after in 1865, leaving Rachel a widow and alone. With a small inheritance, Rachel traveled through Europe between 1867 and 1872 seeking to learn more about the chemistry of ailments and diseases. In the wake of a financial crisis, Rachel returned to the United States where she supported herself by teaching science at a leading women's boarding school, Chestnut Street Female Seminary in Philadelphia, PA, beggining in 1874. Rachel outfitted the school's attic as a teaching laboratory, one of the first instances of American girls being taught chemistry laboratory experiments.

At Harvard:

During most summers between 1875 and 1883, Rachel would visit Cambridge, MA to attend the Harvard Summer Short Course in Chemistry, which accepted female students. Her instructor was Charles Mabery who began teaching the short course as an Assistant in Chemistry while earning his doctorate. From 1874 to 1883, Mabery was the director of the summer chemistry program at Harvard while he pursued his organic chemisry research in the composition of petroleum. Over the years, Rachel ended up publishing three papers with the Mabery in the Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Chemical Journal, becoming the first woman to publish research in a major chemical journal in the United States. Mabery would go on to become a professor of chemistry at Case School of Applied Science (now Case Western) in Cleveland, OH where he taught Albert W. Smith and Herbert Dow, the founder of Dow Chemical Co. In addition to his teaching, Mabery was the director of Standard Oil Laboratory for 35 years, at a time when Cleveland was the center of American petroluem refining in the 1800s. Mabery pioneered the use of infrared spectroscopy for the analysis of distillates and helped develop an electric furnace for smelting.

Career:

Inspite of her formal training and published research, Rachel was unable to find a chemistry professor position in America. Consequently, in 1884, Rachel taught herself German and left for Switzerland, where she began her doctoral studies in chemistry at the University of Zurich, which at the time was the only institution where women were able to earn doctorates in chemsitry. Rachel studied the conversion of phenols to aromatic amines under Professor August Viktor Merz. In 1886, at the age of 48, Rachel was awarded her PhD, making her the first American woman to recieve a doctorate in chemistry.

In 1887, Hudson Nicholson, the only professor of chemistry at the University of Nebraska had convinced the school to a build a second building on campus, called the Chemical Laboratory. Nicholson had argued that chemists could bolster the state's agricultural businesses. Having attended the Harvard summer courses with Rachel, Hudson invited her to teach at the university. Accepting the offer, Rachel became a professor of chemistry at the University of Nebraska, becoming the first woman to become a chemistry professor at a research university in the country. She was promoted to full professor in 1888.

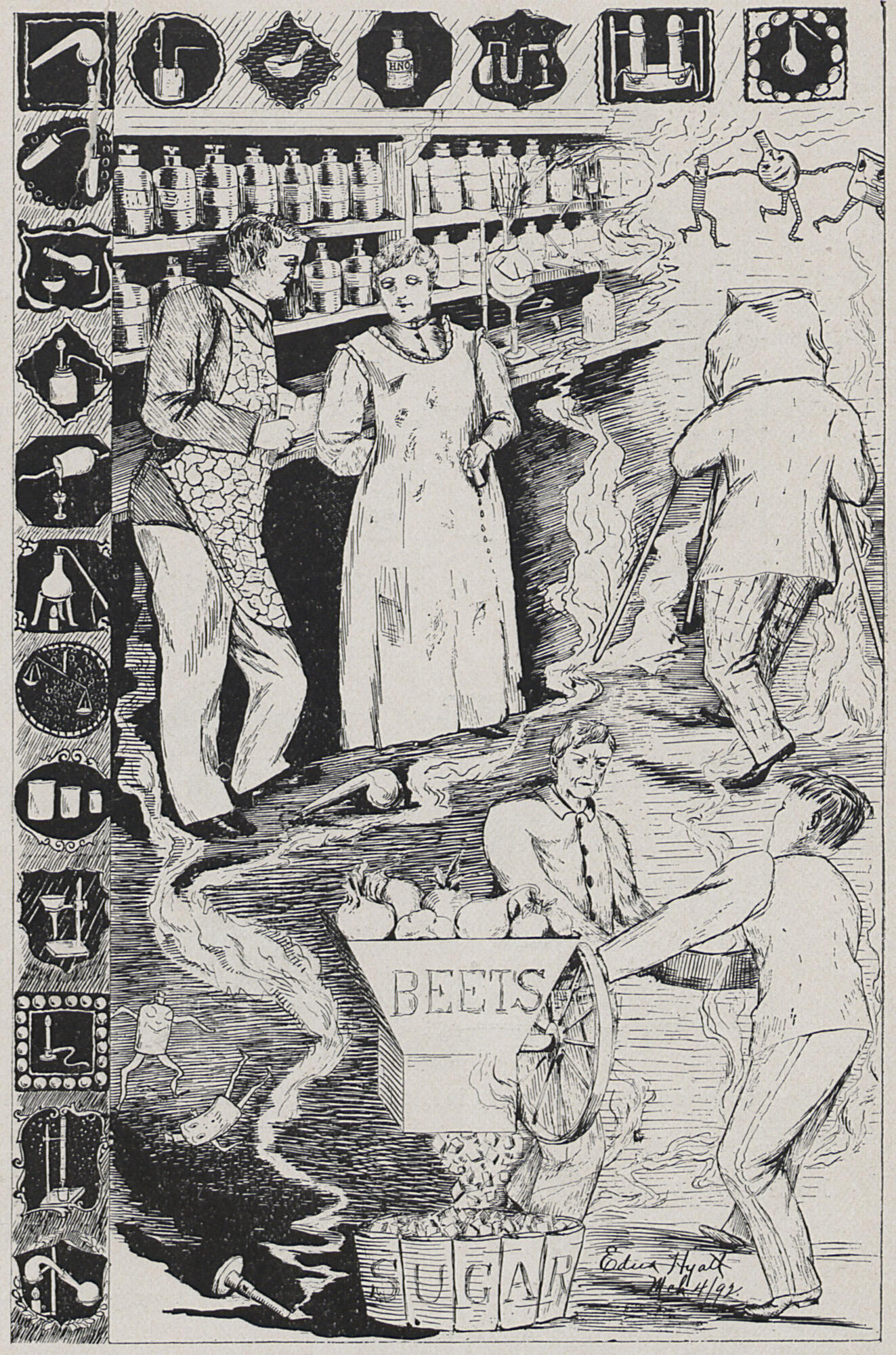

Rachel began researching the sugar content of beets in the 1890s as part of an experimental program to determine whether beets could grow successfully in a northern climate. At the time, sugar beets were a new crop in the United States and important to the farm industry. Through careful analysis of the chemistry of sugar beets and Nebraska soil, Rachel and her colleagues determined that beets could thrive in that relatively cool climate. Based on this knowledge, Nebraska’s beet industry flourished, and, in fact, remains strong today.

Willa Cather, who would go on to become one of America's most celebrated novelists, studied chemistry under Rachel. Cather described her in The Hesparian: "[Rachel] has seen develop, largely by her own efforts, and under eye, one of the largest chemical laboratories in the West. She has seen her lecture rooms crowded by enthusiastic students of all courses and departments... She is one of those instructors who stand not only for a science or a language, but for ideals and all higher culture."

According to the Bulletin of the History of Chemistry, Rachel "undertook responsibility for the laboratory work the project entailed—the determination of the sugar content of the raw product. For this she was provided with some student assistance, but she carried out much of the laborious analytical work herself. Preliminary tests on the 1888 crop gave encouraging results, and by the end of the following year the data she had accumulated provided a convincing demonstration of the potential of the industry in Nebraska. Cultivation costs and yields per acre were reasonably satisfactory, and despite the difficulties caused by inexperience and periods of unfavorable weather, a number of farmers began to take a serious interest in sugar beets. Steps were taken to scale up the operation and establish a sugar factory... In 1892 the university started a Sugar School, one of only two in the country and the only one dealing with beet sugar technology. The instruction offered included a course in elementary chemistry as well as special work in the chemical control of sugar factory operations. Considerable pride was taken in the success of the Experiment Station's sugar beet work, the university catalog published in 1899 claiming that:

'No state in the Union has made a more thorough research into the many questions relating to the growth of the sugar beet, and its manufacture into sugar than has Nebraska, and no small portion of the solution of these questions has been carried on under the provisions of the Experiment Station Act, and by means of the funds coming from the general government...'"

Legacy:

Lloyd taught chemistry at Nebraska until she retired in 1894 due to failing health. During the 1890s and the following decade a remarkable number of women chemists joined the Nebraska Section of the American Chemical Society. Indeed, women were much more prominent in that section than in any other local section in the country. Lloyd herself joined the national society in 1891, becoming the first woman member admitted (except for Rachel Bodley who was given her largely honorary membership at the formation of the society in 1874). In poor health, Rachel moved back to Philadelphia and died in 1900. A short biography of Rachel's life was recovered from a time capsule opened in 2014. The American Chemical Society designated the research and professional contributions of Rachel Lloyd, Ph.D., (1839–1900) as a National Historic Chemical Landmark at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln on Oct. 1, 2014.

Sources/Read More:

- https://unl.libguides.com/c.php?g=51789&p=7196015

- http://acshist.scs.illinois.edu/bulletin_open_access/num17-18/num17-18%2...

- https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/r...

- https://www.acs.org/content/dam/acsorg/education/whatischemistry/landmar...

- https://unlhistory.unl.edu/legacy/rachellloyd/rachellloyd.html

- https://nebraskapublicmedia.org/en/news/news-articles/who-is-rachel-lloyd/

- https://case.edu/ech/articles/m/mabery-charles-f

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rLTJAMQX7ok

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/20021712?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

- https://books.google.com/books?id=wN01AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA700&lpg=PA700&dq#v=o...