Preceptors, then and now

By Caitlin McDermott-Murphy

In the 16th century, expert chemists guarded their hard-won secrets, passing knowledge on to carefully selected apprentices, according to Professor of Chemistry Gary Patterson’s “Preceptors in Chemistry.” Some had only alchemy to share, while others maintained a slow but steady flow of developments in pharmacy and metallurgy (and alchemy, too). Then, in the 17th century, the world’s first chemical preceptors broke down those knowledge barriers and wrote textbooks and delivered lectures, opening chemical education to far broader audiences.

Still, not all chemists excelled in both the lab and the classroom. “Even chemical geniuses can become so focused on their own work that they are not understood by the bulk of their contemporaries,” said Patterson.

Today, hundreds of years later, the Medieval-era title “Preceptor” still exists. The term may be archaic but the need for chemists who can translate the latest research innovations for the next generations will never fade. Both Cambridge and Oxford Universities use the title, as do teaching hospitals. And while Harvard University incorporated the position decades ago, the department got its first just about 15 years ago. Instead of a lecturer’s three-year teaching appointment, preceptors get eight years to innovate within their assigned courses.

“They take these large, chaotic things and bring some order to them,” said Gregg Tucci, the Director of Undergraduate Studies and Senior Lecturer on Chemistry and Chemical Biology. He oversees the department’s four preceptors, also known as non-ladder teaching faculty.

Fresh out of graduate school, the four translate their specialties — from physics to materials and organic chemistry — into digestible coursework, exams, tangible products like organic semiconductors, and ways to calculate and measure real-life problems like the cost savings of recycling, pH level of tap water, and evidence for climate change, among others.

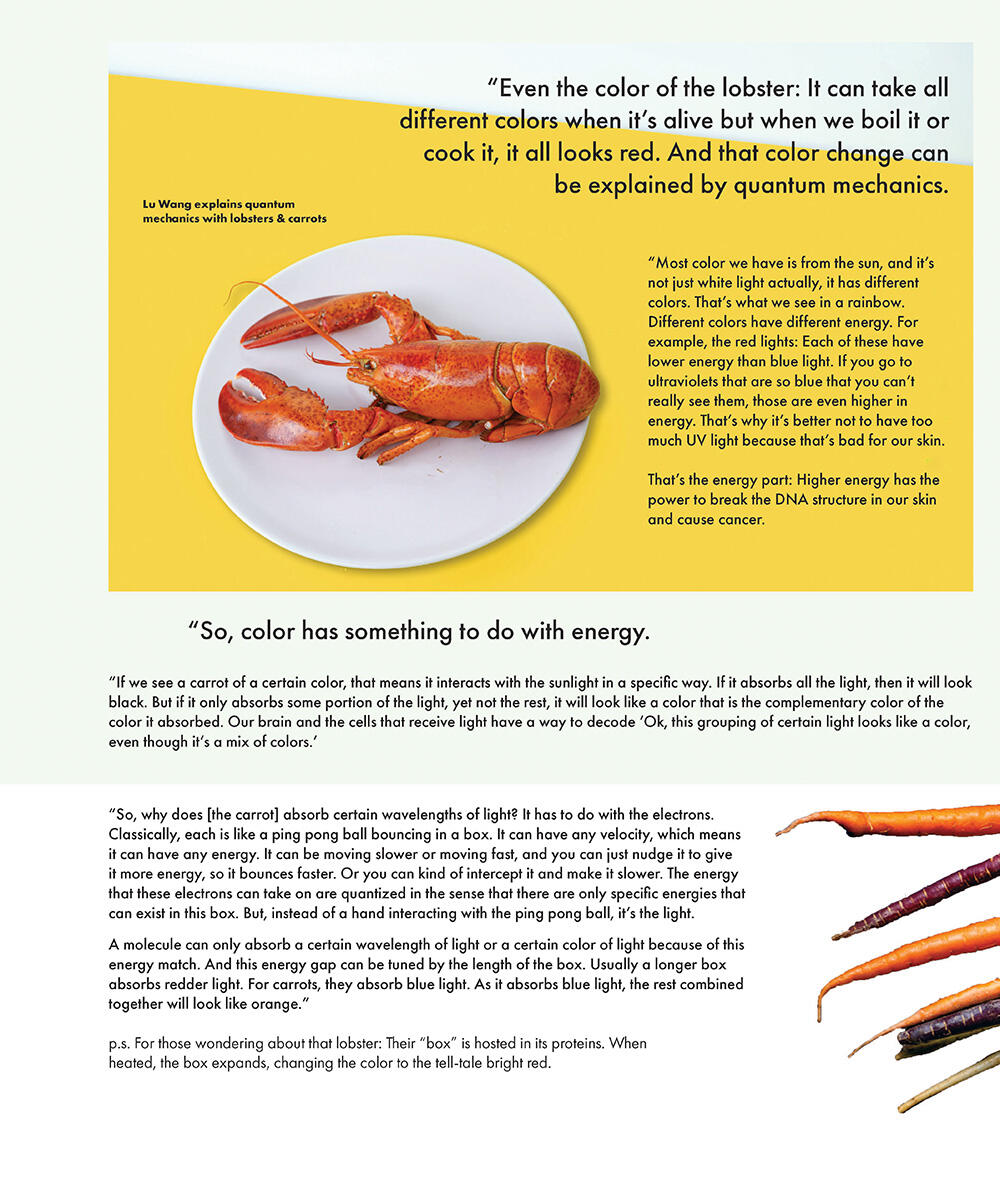

For example, to demystify quantum mechanics, Lu Wang uses lobsters. The crustaceans start off deep green, almost black. But once cooked, their shells shine bright red. That color change comes from a quantum shift — heat energy alters the fundamental structure of certain proteins, changing how they interact with light.

The quantum basis for color — in flowers, carrots, and leafy greens — fascinates Wang, which is why she uses the example with her students. “I thought something that excited me probably will resonate with maybe not all students but hopefully a good portion,” Wang said.

In his Advanced Laboratories courses, Nick Collela trains students to design materials for real-world products like organic semiconductors. “We didn’t get any working devices by the end,” he said. “But they got to see all the fabrication steps and see how the devices are made.”

Mike Mavros tackled STEM test-taking anxiety with a simple pre-exam exercise: For five minutes, students write down what they value — family, friends, hobbies — and why. One student, a high achiever everywhere but in the exam room, increased her score by 20 points.

Tucci said most CCB preceptors end up in faculty-level positions. Mavros is no exception: In August, he joined Wellesley College as their Instructor in Chemistry Laboratory.

Ron Ramsubhag, the newest of the four, can already weave complex chemistry into memorable metaphors. He uses the movie “The Prestige,” in which magicians kill their clones and reappear elsewhere, to help explain carbocation rearrangements. “A hydride migrates over, kills that carbocation, and a new carbocation appears,” he said.

The first in his family to graduate college and to earn a Ph.D., Ramsubhag feels a bit like a misfit at Harvard (the “imposter syndrome” at Harvard is, ironically, common, according to the Graduate School for Arts and Sciences). Ramsubhag’s background is a boon: He has demonstrated chemistry to all levels from middle school students to graduate students and even his parents, who didn’t know what atoms were until their son figured out a simple way to explain.

CCB’s preceptors train Teaching Fellows, invent new problem sets, and coach students. They design novel grading technology that can uncover common student mistakes and provide automatic feedback. They are the engines that keep courses moving forward.

“We really could not do what we do without preceptors,” Tucci said. “If you took them away it would be a giant disaster.”